Author: R&D Team, CUIGUAI Flavoring

Published by: Guangdong Unique Flavor Co., Ltd.

Last Updated: Feb 04, 2026

Analyzing Natural Aromas

Flavor is where chemistry meets experience. This article is a practical, technical guide for food and beverage professionals who design, evaluate, and manufacture flavors. It explains the chemical building blocks of taste and aroma, the pathways by which those molecules form and change, how they interact with complex food matrices, and the analytical and sensory methods used to quantify and qualify them. The goal is actionable understanding: apply these principles to design stable, evocative, and regulatory-compliant flavors that succeed on shelf and delight consumers.

Flavor drives purchase, repeat consumption, and brand loyalty. For manufacturers of food and beverage flavors, understanding the chemical underpinnings of flavor is essential for three commercial objectives:

This article translates the science into formulation- and process-level guidance so product developers and technical teams can deliver reliable, delightful flavors at scale.

“Flavor” is the combination of taste, aroma, and trigeminal sensations (cooling, burning, astringency). Chemically:

Understanding the distinction is crucial: many flavor strategies center on volatile delivery (to shape aroma) while modulating non-volatiles to tune taste and mouthfeel.

Below are the primary chemical families encountered in flavor work, with typical sensory contributions and formulation notes.

Understanding each class’ volatility, odor threshold, reactivity, and perceptual profile is core to successful flavor design.

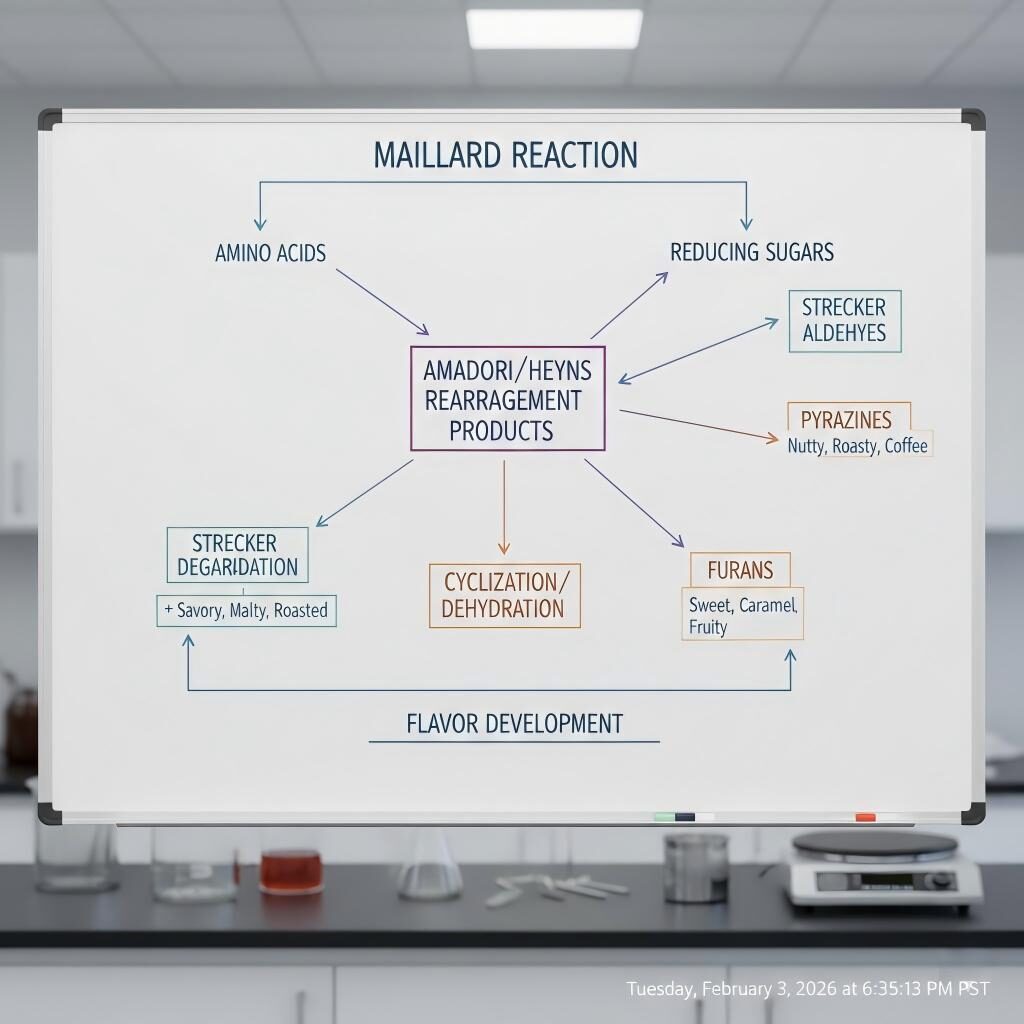

Maillard Reaction Pathway Diagram

Flavor compounds originate from several pathways that are either intrinsic to raw materials or created during processing:

A reaction between reducing sugars and amino acids during thermal processing produces hundreds of volatile and non-volatile compounds (pyrazines, furans, Strecker aldehydes) that create roasted, caramel, and savory notes. The Maillard chemistry is complex; controlling temperature, time, pH, and reactant stoichiometry guides the flavor outcome. Extensive review literature documents mechanistic steps and major classes of Maillard-derived volatiles.

Pure sugar thermal decomposition yields furans and other sweet/burnt notes distinct from Maillard products (which require amino donors).

Lipids break down (enzymatically or thermally) to free fatty acids, which oxidize through autoxidation or lipoxygenase pathways to form aldehydes, alcohols, and ketones (green, fatty, warmed-buttery notes). Control of oxygen exposure and antioxidant usage is critical to avoid off-flavors.

Yeast and bacteria generate esters, alcohols, and phenolics during fermentation (beer, wine, cheese) — a powerful route to complexity. Process parameters (strain, temperature, nutrient regime) tune the bouquet.

Enzymes like glycosidases, lipoxygenases, and glycosyltransferases release or modify flavor precursors (e.g., glycosidically bound terpenes in fruits become free aromatic terpenes upon enzyme action).

A common design failure is ignoring the food matrix. Flavor perception derives from volatiles released into the headspace above a food, and that release is controlled by matrix interactions.

The equilibrium concentration of a volatile in the headspace depends on its partition coefficient (K) between the food matrix and the gas phase. Highly lipophilic volatiles partition into fats (reducing headspace concentration), while hydrophilic volatiles favor aqueous phases.

Proteins, polysaccharides, and polyphenols can bind volatiles via hydrophobic pockets, π–π interactions, or covalent adduct formation. These interactions affect flavor intensity and release profile (e.g., protein-rich systems often show muted aroma). Adjusting fat content, processing pH, or using release agents can restore headspace concentration.

In emulsions (dressings, beverages with oil phases), the oil volume fraction and droplet size control volatile retention and release. Smaller droplets increase surface area and can accelerate release during oral processing.

Higher temperatures increase volatility and speed release, but they also accelerate chemical transformations. Pasteurization, baking, extrusion, and frying are not only preservative/texture steps — they are flavor generators and modifiers.

Analytical chemistry translates sensory impressions into measurable targets. These are the primary tools used by flavor chemists:

GC–MS is the workhorse for volatile identification and quantification. Coupled sample-preparation methods such as headspace solid phase microextraction (HS-SPME) concentrate volatiles for analysis. Quantitation requires careful internal standards, response factor calibration, and often stable isotope labelled standards for accuracy.

GC–O pairs separation with human sniffing at the detector to identify odor-active peaks (aroma extract dilution analysis, OSME methods). It connects chemical peaks to perceived aroma potency; a compound with low abundance but strong odor activity may be a key driver note.

Used for non-volatile flavor precursors, polyphenols, and reaction intermediates.

Quantitative descriptive analysis (QDA), time–intensity, and consumer testing combine with GC data and multivariate statistics (PCA, PLS) to create predictive models linking chemical profile to perception.

Practical note: analytical numbers (µg/kg, ng/L) matter, but so does odor threshold. A compound present at µg/kg levels can dominate aroma if its odor threshold is orders of magnitude lower than other constituents.

(For industry training and the state of flavor analytical methods, see resources from the Institute of Food Technologists.)

Flavor stability is a core commercial requirement. Common degradation pathways include:

Oxygen reacts with unsaturated compounds, leading to loss of desirable notes and the formation of off-odors (peroxides, aldehydes). Mitigation: oxygen-scavenging packaging, inert gas blanketing, chelators, and antioxidants (careful selection to avoid reactions with flavor components).

Esters and glycosides hydrolyze under acidic or basic conditions to yield alcohols or acids, shifting profile over time. Mitigation: pH control, ester selection (steric hindrance), and microencapsulation.

High sugar/protein matrices can continue Maillard chemistry in storage at elevated temperatures, generating new volatiles or brown pigments. Mitigation: control of water activity (aw), storage temperature, and reactant concentrations.

Volatile components can diffuse through packaging or evaporate from open systems. Mitigation: barrier films, headspace control, and use of lower vapor-pressure congeners or controlled-release matrices.

A robust shelf-life program combines accelerated aging (Arrhenius modeling), analytical monitoring (target compounds + markers of degradation), and sensory checkpoints.

Matching sensory goals with process and stability constraints requires engineered delivery. Common solutions:

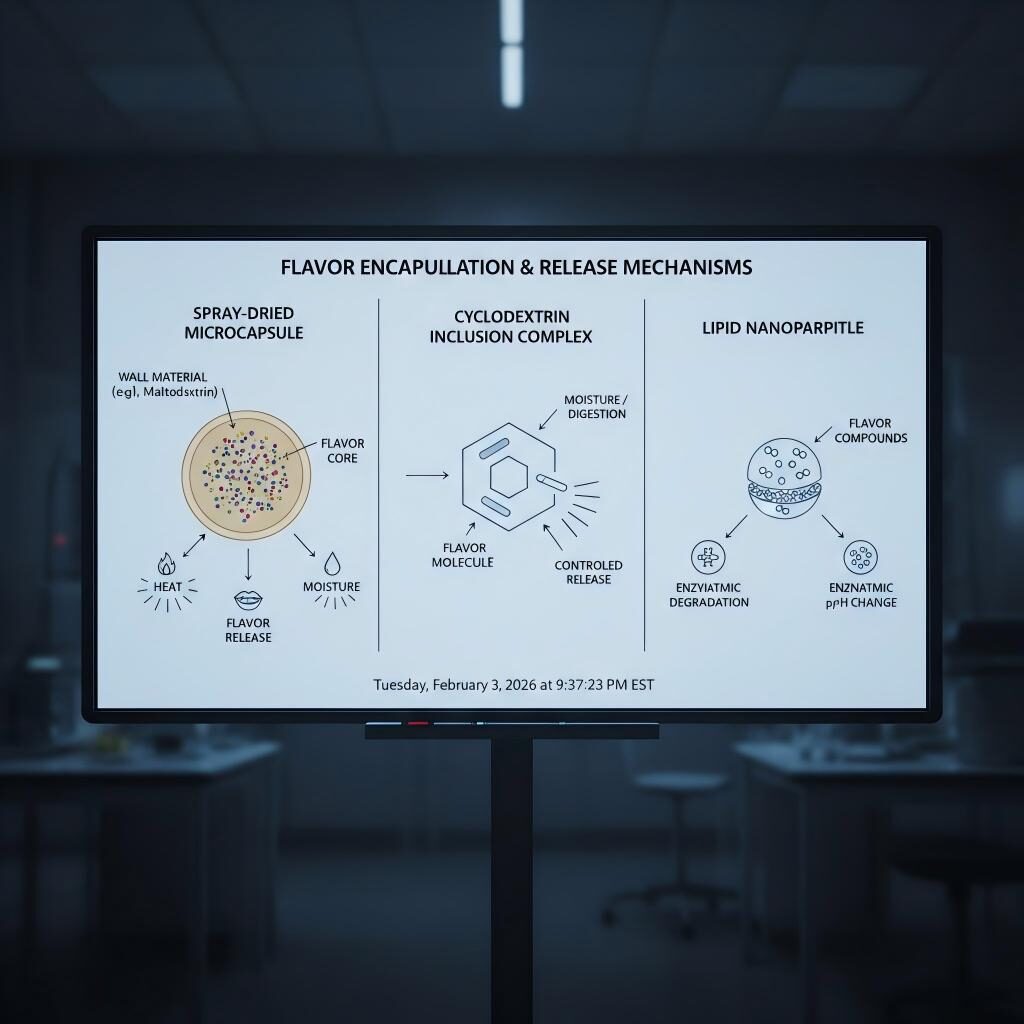

Encapsulating flavors in carbohydrate or protein shells masks reactive volatiles, protects against oxidation, and enables dry blending. Spray-dried powders are ubiquitous in bakery and instant beverage systems.

Cyclodextrins form host–guest complexes that sequester small volatiles, releasing them upon dilution or mastication. Useful for masking off-notes or stabilizing thiols and aldehydes.

Liquid flavors or oil-dissolved actives packaged in lipid carriers can enhance solubility in fat-rich matrices and modulate release. Nanoemulsions may increase bioavailability and headspace release after oral breakdown.

For functional applications, co-formulating enzyme substrates or controlled microbial components can generate in-situ flavor during processing or storage — but regulatory and stability constraints must be carefully managed.

Design flavors using precursors that generate the active volatile upon a trigger (heat, pH change, enzymatic action). This helps in systems where the processing step is the flavor generator (e.g., roasted notes formed during baking).

Practical formulation checklist:

Regulatory compliance is non-negotiable. In the U.S., flavor ingredients may be used as food additives or as GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) substances, and manufacturers must ensure correct labeling and safety documentation. The FDA provides guidance and maintains GRAS inventories and resources for compliance.

Important practical points:

For authoritative historical/regulatory context and classification schemes, industry summaries and agricultural/food service guidance (USDA/AMS) are useful references.

Analytics give chemical fingerprints; sensory testing shows what matters to consumers. A combined approach includes:

Use GC-O to identify key odorants, then target those in reformulation or stabilization. Not every abundant compound matters; odor activity values (concentration/threshold) prioritize targets.

Flavor Encapsulation & Release Mechanisms

Below are condensed, practical examples that illustrate the application of flavor chemistry principles.

Problem: Loss of fresh lime/bergamot top notes over 3 months.

Diagnosis: Highly volatile monoterpenes (limonene, linalool) partition into headspace and oxidize; packaging permeation observed.

Solutions implemented:

Problem: Want pronounced toasty/roasted notes in low-moisture cake mix; pre-bake flavor generation limited.

Tools used:

Problem: Plant-based drink needs buttery mouthfeel without rapid oxidative rancidity.

Approach:

Note: these tables are suggested for inclusion in the corporate blog as visual assets or downloadable datasheets.

Sensory Analysis & Flavor Blending

If your R&D team would like a technical exchange, stability screening protocol, or a free sample tailored to a specific product matrix (beverage, bakery, dairy alternative, or savory), our flavor scientists are ready to collaborate. Contact us for a technical consultation + sample kit so we can match targeted aroma compounds, select protective carriers, and run pilot stability tests against your processing conditions.

Request a technical exchange or free sample:

| Contact Channel | Details |

| 🌐 Website: | www.cuiguai.cn |

| 📧 Email: | info@cuiguai.com |

| ☎ Phone: | +86 0769 8838 0789 |

| 📱 WhatsApp: | +86 189 2926 7983 |

| 📍 Factory Address | Room 701, Building 3, No. 16, Binzhong South Road, Daojiao Town, Dongguan City, Guangdong Province, China |

Copyright © 2025 Guangdong Unique Flavor Co., Ltd. All Rights Reserved.